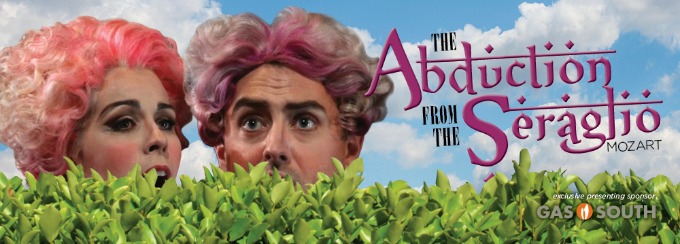

THE ‘WHY’ BEHIND MOZART’S EARLY FARCE, A MERRY STEW OF TURKS, SEX AND, YES, SLAVERY

Mozart’s ‘The Abduction From the Seraglio” opens The Atlanta Opera season with performances Oct. 8, 11, 14 and 16.

::

ISLAM, KIDNAPPING, SEX and slavery — these are risky conversation topics for holiday gatherings. But not in 1782. Mozart’s The Abduction From the Seraglio places the action outside a Turkish harem. It isn’t a probing exploration of religion or human rights, though, it’s farce.

Based on Belmont und Constanze by Germany’s Christoph Friedrich Bretzner, the Turkish palace is but a backdrop to the drama of two women, their lovers and the powerful Muslim men who seek the women’s affections. Let’s look at why Mozart chose this story.

For nearly 500 years, the Ottoman Empire had expanded its range, conquering and plundering whole civilizations. Turkish forces twice attempted (and failed) to take Vienna — the second siege lasted two months and ended in September 1683. Mozart’s father would have known people who lived through it.

Even as European slavers were shipping Africans to the Americas, North African pirates were selling Europeans to the Turks. Mozart knew of charities that paid ransoms to bring people home.

One might expect Mozart’s Vienna, then, to despise the empire to the south — but no — all things Turkish were in vogue. Tales of European ladies serving as sex slaves in exotic lands became popular fiction. People commissioned portraits of themselves clothed in fabrics from Istanbul. And merchants opened establishments serving a beverage called coffee. (Legend has it that the Viennese coffee craze began after the siege of 1683 when the fleeing army left behind bags of strange-smelling beans.) Mozart’s nod to Turquerie offers a lovesick Pasha and an extraordinary act of mercy.

Ears in the 21st century might strain to hear exotic sounds in Mozart’s score. In 1782, the Viennese recognized echoes of the Ottoman Empire. The bass drum and the jingling of cymbals, triangles and piccolos conjured the military bands that had terrorized their city in 1683. In Abduction, they spin a musical costume around Turkish characters.

Turning travel into music

Composing The Abduction came at a major intersection in Mozart’s life. At 25, the former child prodigy had just left home for good.

His father, Leopold, was a stage parent. A respected musician, he cultivated his son’s genius from an early age and touted him in courts across Europe. British scholar Daines Barrington presented an eyewitness account of meeting with the 8-year-old Wolfgang in 1764. Barrington selected a complex score in five parts and presented it to the boy seated at the harpsichord. Barrington wrote:

“The score was no sooner put upon his desk, than he began to play the symphony in a most masterly manner, as well as in the time and style which corresponded with the intention of the composer.”

Barrington’s account reveals something elemental about Mozart: He could instantly comprehend and master new musical styles. From his travels, he absorbed everything from Italian opera to the sacred music of J.S. Bach. In The Abduction From the Seraglio and operas to come, he throws that experience into his scores, giving opposing characters opposing musical styles.

Although Mozart remained deeply devoted to his father, he defied him twice in the year or so surrounding this opera’s composition. In 1773, Leopold had procured for Wolfgang a position in the court of the Archbishop of Salzburg. While Leopold knew his place in this world, Wolfgang resented it. As a low-ranking servant, Mozart suffered many humiliations at the hands of his boss. By spring 1781, he begged for release. He succeeded in June, getting himself booted out of Salzburg — literally “with a kick in the arse.” He left for Vienna, seeking fame and fortune.

Creating a ‘singspiel’

By July, Mozart had secured a commission for an opera. Vienna’s Burgtheater, sponsored by Emperor Joseph II, offered him Bretzner’s libretto to The Abduction From the Seraglio, reworked by Gottlieb Stephanie.

The piece was to be a “singspiel,” taken from the German words singen (to sing) and spiel (play). Singspiel juxtaposes dialogue and music, similar to the Broadway musical. Treating the job like an audition, Mozart wrote to his father:

“As we have given the part of Osmin to Herr Fischer, who certainly has an excellent bass voice (in spite of the fact that the Archbishop told me that he sang too low for a bass and that I assured him he would sing higher next time), we must take advantage of it, particularly as he has the whole Viennese public on his side. But in the original libretto Osmin has only this short song and nothing else to sing.”

Mozart changed the story to fit the singer. The Turkish overseer became a major comic character: stupid, surly, malicious. The music fits him, lacking the elegance and harmonic complexity of his European captives — which is not to say it’s easier to sing. Osmin’s Act 3 aria “O, wie will ich triumphieren” is famously difficult and showcases Fischer’s ability to sing a low D.

While composing Abduction, Mozart ponders the conundrum of writing beautiful music about anger.

“Passions, whether violent or not, must never be expressed to the point of exciting disgust, and as music, even in the most terrible situation, must never offend the ear, but must please the listener.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SRdsHdnCUzM

Mozart’s solution was to give the singer more notes. When his noble heroine Konstanze is confronted by a fate worse than death, she lets it fly, singing a flurry of runs, trills and leaps. Her feisty servant, Blonde, defies Osmin in similar virtuosic fashion, singing, “I am an Englishwoman, born for freedom.” (It’s interesting that Mozart’s egalitarian-minded servant is English, a safe distance from Austria, given that he was composing at the command of the Austrian Emperor.)

The Abduction From the Seraglio, which opened July 16, 1782, was a hit. Profits poured into the Burgtheater, from which Mozart received a modest flat fee.

Less than a month later, Mozart defied his father once more and married Constanza Weber. That he courted Constanza while creating the operatic heroine Konstanze was purely coincidence; that he delighted in the irony was pure Mozart.