THERE IS NO BOOK YOU CAN READ, no documentary you can watch, and nothing I can tell you that will prepare you for the overwhelming emotional experience of standing less than 10 feet from a family of wild mountain gorillas in northern Rwanda.

We could discuss the swell of anticipation that begins the moment you pull into the parking lot of Parc National des Volcans, where hundreds of hikers, trackers, porters and guides assemble every morning to coordinate one of the world’s most exclusive treks. We could describe the dense undergrowth and often steep inclines your group must navigate to reach the gorillas’ preferred nesting grounds. We could talk about how your heart pounds the moment your guide instructs you to drop your backpacks and walking sticks because “the gorillas are very close.”

But there’s nothing that can compare with standing awestruck in the midst of a 6-foot-wide clearing in the foothills of Mount Sabyinyo as a 3-month-old gorilla pounds its tiny chest in a comical display less than six feet from your face while his mother nibbles on greenery nearby. Or having to quickly move out of the way as Big Ben — an adult gorilla with male-pattern baldness — uses a bending tree branch to descend and executes a perfect somersault right where you just stood.

Keep in mind that this was just the first five minutes of our hour-long visit to the 13-member Sabyinyo gorilla group, which is led by Guhonda, the largest silverback (weighing in at about 485 pounds) measured in Volcanoes National Park to date.

Dian Fossey’s legacy

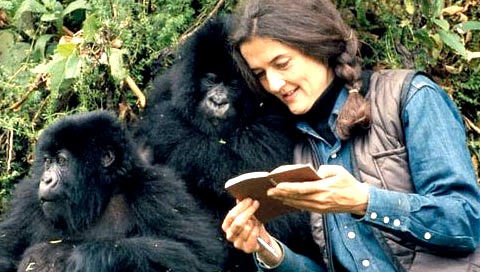

None of this would be possible today were it not for the groundbreaking work of Dian Fossey, who’s probably best known for her best-selling autobiographical book, Gorillas in the Mist, and the 1988 film version starring Sigourney Weaver (and nominated for five Academy Awards).

Along with Jane Goodall and Biruté Galdikas, Fossey was one of three iconic primatologists influenced and assisted by legendary archaeologist and paleontologist Louis Leakey. Known as the Trimates, or “Leakey’s Angels,” they made huge strides in the field research of primates in their natural habitats, which Leakey believed was crucial to unraveling the mysteries of human evolution. And, they did it in an era when women in scientific research were considered highly controversial.

San Francisco-bred Fossey became the second of Leakey’s “angels,” even though her background was in occupational therapy for children. She first got his attention during a life-changing 1963 visit to East Africa. They met in Olduvai Gorge, where she made a vivid first impression by breaking her ankle, falling into an excavation and vomiting on a giraffe fossil.

She encountered Leakey again three years later at a lecture in Louisville, Ky., where she showed him articles she’d written about her African adventures. Impressed by her pluck, Leakey hired her for a long-term study of mountain gorillas in the Virunga Mountains, which border the Congo, Rwanda and Uganda. At the time, little was known about the reclusive species.

Enduring temperatures below 40 degrees, carrying gear on their backs, and traveling through thick vegetation and mudslides, Fossey and her team established the Karisoke Research Center at 12,000 feet above sea level on an extinct Rwandan volcano. They gradually familiarized the gorillas with humans by carefully mimicking the gorillas’ sounds and body language.

A National Geographic cover story made Fossey and her mountain gorillas famous, and her work influenced nearly every aspect of gorilla conservation today. Unfortunately, her interactions with locals were less productive. Her aggressiveness in protecting the gorillas made enemies among government officials and indigenous peoples, many of whom poached animals in the gorillas’ forests to feed their families.

On Dec. 26, 1985, Fossey was killed in her sleep. Her murder has never been solved, and her marked grave at the remote Karisoke camp has long since fallen into ruin. But the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International (based at Zoo Atlanta) continues her work, helping Rwanda’s mountain gorilla population grow from 254 in 1981 to about 500 today.

[Watch Dian Fossey at work and play with the mountain gorillas.]

Ecotourism dollars talk

With trekking permits at $750 and 10 gorilla groups attracting 80 hikers per day, the mountain gorillas are now at the epicenter of Rwanda’s thriving ecotourism industry. Locals help protect them because they have a financial stake in their conservation: Most families in the area have at least one member who works as a tracker, porter, guide or souvenir vendor.

Our colorful guide, Francois Bigirimana, is among the park’s oldest. He’s been working here since 1978, and served as a porter for Fossey in the early 1980s. His love and respect for the gorillas is obvious as he talks about their family units, what they eat and how humans should behave around them.

You’re not supposed to get closer than six feet, but the gorillas clearly did not get that memo. Besides Big Ben’s acrobatic antics, a female strolls through our group as we’re photographing Guhonda feeding on leaves, gently putting her hand on someone’s shoulder as she passes by.

Right before our magical hour is up, we spend several breathless minutes in a nest beneath foliage, surrounded on all sides by mothers, toddlers and infants lying down before their midday naps. It’s one of the most powerful and surreal moments of my life.

Putting those feelings into words couldn’t possibly do them justice. It’s something you simply have to experience for yourself.