The world premiere of “Edward Foote” runs March 27-April 19 at the Alliance Theatre’s Hertz Stage. It’s recommended for ages 16 and older.

::

YOU CAN’T PUT your finger on it, but something’s afoot in Edward Foote. What could it be? Not so fast. A scribe as seasoned as Phillip DePoy will build the tension gradually.

The author of 15 novels, two nonfiction titles and more than 40 produced plays wants his audience to ponder and pry, to wonder why, maybe even squirm a little.

For Atlanta’s DePoy, the arrival of Edward Foote on the Alliance Theatre stage marks the end of a journey that took root in 1969.

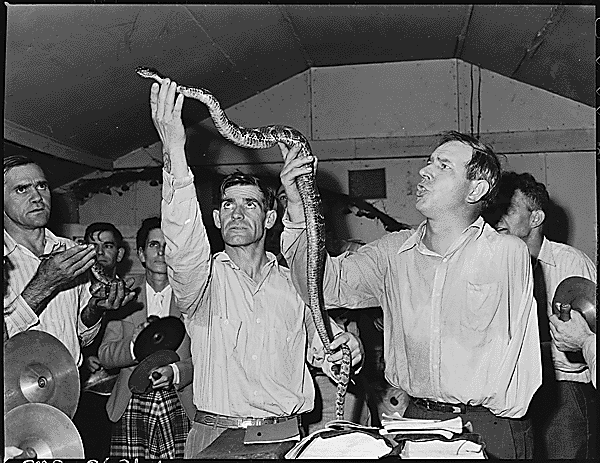

He was a student at Georgia State University, an English major with a folklore minor. He remembers being “completely knocked out” during a student research trip to a church in the North Georgia mountains where he witnessed a Pentecostal service with snake handling, people talking in tongues and screaming.

“A guy was pulling snakes out and started hitting himself in the face with them,” DePoy recalls. “He was even daring a rattlesnake to bite him. I had never experienced such a thing. I mean, these folks were completely transformed by what was happening.

“My first thought was that I was trapped in this building, where everyone was hysterical. My second thought was, ‘This is really great theater.’ That was the beginning of the play for me.”

On his website, DePoy says he tells “ancient stories in a new way.” He continues: “Through every fashionable literary movement, through every historical context, before civilizations rise and after they fall, we repeat the events in different ways.”

Almost everything he writes has some basis in folklore, mythology or classic literature. There are witches, ghosts, time travelers, curses – or in the case of Edward Foote, a stranger who comes to call.

DePoy calls Edward Foote “a twisted take on the Oedipus story, set in Appalachia during the Depression. So you can bet it’s a happy little play. Plus there’s music.” The piece includes authentic Sacred Harp (or shape-note) music and traditional Appalachian songs.

He selected the songs for Edward Foote with input from his younger brother Scott, an actor-musician who’s heavily involved in Sacred Harp singing. Both brothers compose music and come by it naturally; their dad played French horn with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra.

DePoy sees Edward Foote as the first in his “Appalachian trilogy.” The next two plays will share themes with the medieval romantic legend of Tristan and Isolde, and Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

DePoy sees Edward Foote as the first in his “Appalachian trilogy.” The next two plays will share themes with the medieval romantic legend of Tristan and Isolde, and Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

Southern Appalachia, where DePoy has lived and worked at times, is a frequent setting for his work. He has an ear for the language, in which a flower may be called “right pretty,” while someone upset can “seem mite distress.”

“I’ve had the good fortune to know the people who belong to that region,” he says. “I’ve met them, spent time with them.” He set Edward Foote in the Depression because his story needed a time, place and small community that were as bare bones as possible.

“While the Depression was horrible for all, it was literally killing those in Appalachia,” DePoy says. “Almost half of adults died from starvation or lack of water. Many women died in childbirth. According to some records, the infant mortality rate was 90 percent: nine in 10 babies died. People who had had nothing now had negative nothing – and nothing that could be done about it. It was like a biblical plague.”

Oh, that thing you can’t quite put your finger on in Edward Foote? Call it a sense of quiet, approaching gloom or doom. How does DePoy craft this subtle buildup of dread, or anticipation, or suspense?

It comes from “more than 40 years of writing every day, and studying and thinking about writing,” he says. And watching Alfred Hitchcock films and reading Raymond Chandler novels to figure out the way the tension mounts.

When he gets down to talking about how he builds toward a big reveal, it turns out he’s a mystery writer whose actual process is mysterious.

“I know this sounds a little insane,” he says, “but I’m not sure what it is that does the writing. It’s certainly not my conscious mind. Something works itself out, then I type it on the page. For me, the creative process is a sort of ineffable experience. Like something else does the writing and I’m just there to do the typing. Seriously.”