“GANDHI SPEAKS FOR US,” reads a little scrap of paper with worn edges, creased from being folded and refolded. The words are in old-fashioned typing. “Say ‘no’ to violence but ‘yes’ to life,” they urge.

It’s the note that the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. once carried in his wallet. It now lies under glass at the new National Center for Civil & Human Rights in downtown Atlanta. In this building, the civil rights movement of 50 years ago is linked to a broad human rights struggle today.

Despite its rather imposing name, the surprisingly compact center of 43,000 square feet has little of an institutional feel. Its sentiments spill out of its high windows like a message to the world.

In some ways the building has a bunker-like quality. Compared with the surrounding skyscrapers, it’s low to the ground. But, the wood-fiber cladding that wraps around two sides functions like protective wings, sheltering the tall glass front. There’s something of a bird in this piece of architecture.

In some ways the building has a bunker-like quality. Compared with the surrounding skyscrapers, it’s low to the ground. But, the wood-fiber cladding that wraps around two sides functions like protective wings, sheltering the tall glass front. There’s something of a bird in this piece of architecture.

To reach the museum, you’ll walk through Pemberton Place — the blandly landscaped area near Centennial Olympic Park — and pass tinny music pouring from the World of Coca-Cola. You’ll enter the exhibit “Rolls Down Like Water: The American Civil Rights Movement” and immediately see black-and-white TV footage of 1960s events, such as demonstrators in Birmingham being hit by water hoses.

You’ll also see:

- An actual lunch counter from a sit-in.

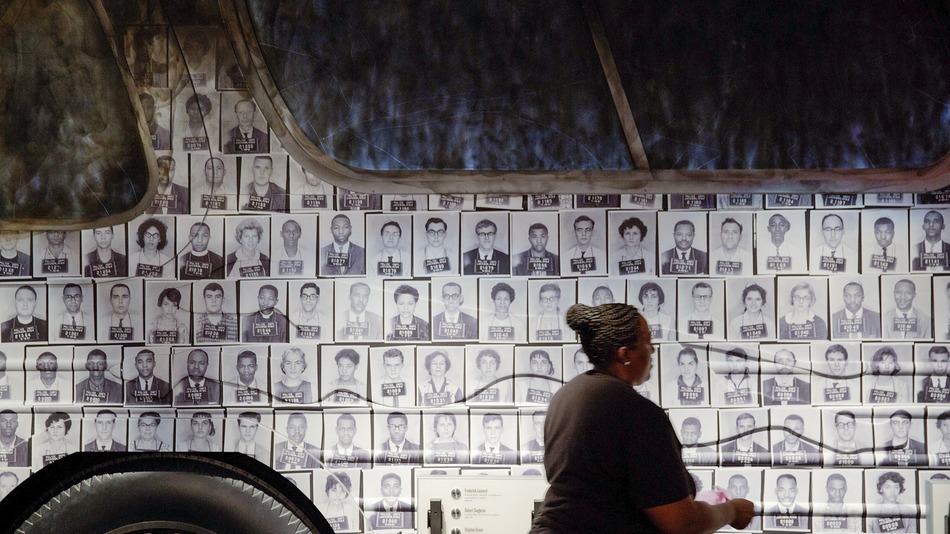

- An interactive wall of images of Freedom Riders that comes with audio.

- A wide curving screen showing images from the 1963 March on Washington, accompanied by the music of Mahalia Jackson, Odetta and Joan Baez.

- Stained-glass images of the four young girls killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham.

- Footage of King’s body being returned to Atlanta.

- Paintings by Georgia artist Benny Andrews.

“It’s overwhelming,” a retired teacher from New Mexico says. With each section of the exhibit, she says, she’s reminded of events that made news 50 years ago and included friends of hers who marched in Selma.

Visitors will next step into a bright, circular room with vertical video screens and an infectious drumbeat. Video features people around the world who are active in movements for justice. The question becomes: What are you going to do?

GOING TO THE NEXT LEVEL

Upstairs is a space that seems startlingly familiar. Its gleaming white walls, silver mirrors and glowing hardwood floors resemble a high-end department store. Images that are nearly life-size can be seen on mirrored surfaces. Words such as “refugee,” “disabled,” “man,” “mother,” “Protestant,” “Hindu” are etched into them.

You’ll see Jitman Basnet, a lawyer and journalist who was imprisoned and tortured in Nepal. His voice says: “All that time, I was blindfolded and my hands were tied behind my back.”

You’ll also see images and hear from people deeply involved in human rights struggles, from women’s rights to LGBT issues, along with immigrants, refugees and the disabled.

“We must believe in the importance and strength of our own words,” says young Pakistani activist Malala Yousafzai.

“Why do people persecute other?” asks another.

This exhibit, “Spark of Connection: The Global Human Rights Gallery,” is centered around the Universal Declaration of Human Rights created by the United Nations after World War II. Former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who chaired the committee, is pictured along with King, Mohandas Gandhi, Soviet dissident Yelena Bonner, Czech playwright-turned-president Vaclav Havel, Nelson Mandela and Estela Barnes de Carlotto, whose pregnant daughter disappeared during the U.S.-supported Dirty War in Argentina in the 1970s.

This exhibit, “Spark of Connection: The Global Human Rights Gallery,” is centered around the Universal Declaration of Human Rights created by the United Nations after World War II. Former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who chaired the committee, is pictured along with King, Mohandas Gandhi, Soviet dissident Yelena Bonner, Czech playwright-turned-president Vaclav Havel, Nelson Mandela and Estela Barnes de Carlotto, whose pregnant daughter disappeared during the U.S.-supported Dirty War in Argentina in the 1970s.

VISITORS HAVE THEIR SAY

Don’t miss the small room where you can add your voice and photo to the conversation, a nook clearly meant to encourage thoughts about how we define ourselves and how we define injustice.

The Morehouse College Martin Luther King Jr. Collection is here, too. It includes King’s briefcase and handwritten speeches with notes jotted in the margins.

The small scrap of paper from his wallet is here, too. It returns us from the American civil rights movement and global human rights struggles to the intensely personal conviction of one man who gave his life fighting injustice.