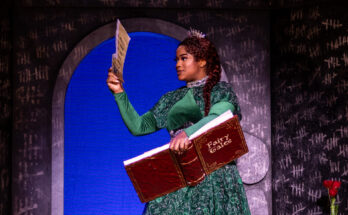

A German province, 1891. A world in which adults have all the power and dole out discipline with an iron fist and no sentiment. This is where the beautiful young Wendla observes the mysteries of her maturing body and wonders aloud where babies come from — until her mother tells her to shut up and put on a proper dress.

Atlanta, 2010. Imagine this century-old story propelled by contemporary rock music and told by actors with super-modern headset microphones but starchy-stiff 19th-century costumes. It’s in this edgy, incongruous, layered landscape that Jake Epstein and 16 friends make a living six days a week. As Melchior, the love-struck student who fancies Wendla (a role originated by Lea Michele of TV’s “Glee”), Epstein often is at the center of a tale he describes as a “coming-of-age story about teenagers living in a repressive society and discovering their sexuality.” The score he calls “alternative rock meets Joni Mitchell.”

Melchior, Epstein says, is “charismatic and atheistic, with an inner need for change.” He, Wendla and best buddy Moritz — all students at an impossibly strict school — form a curious yet innocent trinity done in by the morals of the day. They deal with love, lust, pregnancy, abortion and even less palatable experiences.

This world without light was first envisioned by German playwright Frank Wedekind just before the turn of the 20th century. A play without music, his heavily censored Spring Awakening opened in Germany in 1906. It debuted in New York in 1917, had one performance, was deemed obscene and then shut down. History shows that Wedekind, a friend of Samuel Beckett and fan of August Strindberg, dared to deal with issues of sexual freedom and release, problems of puberty, moments of ecstasy between the sexes, and moments of misunderstanding and violence. In his era, these themes were deemed pure pornography.

So why would a musical’s modern-day creators want to take on such a piece? Steven Sater, who wrote the book and lyrics, fell in love with Wedekind’s play while in high school. In 1999, in the wake of the Columbine shootings, he shared it with composer Duncan Sheik, who, as the story goes, was intrigued but not interested in doing a typical musical in which characters speak one moment and serenade each other the next.

So they conceived Spring Awakening as a piece of musical theater and a pop-rock album. They would use the songs as interior monologues, voicing only the thoughts and feelings of the characters. With the help of director Michael Mayer, that concept stuck. Even in group numbers, Epstein says, characters are immersed in their own thoughts and feelings, not one another.

It worked, splendidly. In a season that also birthed Grey Gardens, the whodunit Curtains and Mary Poppins, Spring Awakening won eight Tony Awards — best musical, book, music, choreography, direction, orchestrations, lighting and featured actor (for John Gallagher Jr., who played Moritz).

Epstein first saw Spring Awakening with his parents and older sister on Broadway, long before he auditioned. “I grew up in a very musical family, but I never connected to the classic American musical,” he says. “And then I saw this. I was on the edge of my seat. I had never seen anything like it.”

His parents? Well, they didn’t discuss it until Epstein booked the tour. “I think they really loved it,” he says, looking back. “I think they certainly were uncomfortable and were in shock at times; it certainly challenges you. When they came to see me in it, they felt that the more times you see it the more you come to understand it.”

Atlanta is the 11th city the 23-year-old Canadian will see on this tour that, he says, has given him an interesting view of the regional morals of America. Washington, D.C., embraced the show. Kansas City, Mo., was silent, with a lot of walkouts. Denver was very appreciative but very quiet. Austin, Texas, “really connected” with it. Fort Myers, Fla., where the show opened the day before we spoke, seemed polarized, with some audience members loving it and others being shocked by it.

“It’s really interesting,” Epstein observes. “In movies and TV, sex is a main topic. [However,] when you are talking about it onstage, it can make people very uncomfortable.

“I always feel like we’re doing a good job when people get offended,” he says. “It’s not a bad thing to think outside the box sometimes. We’ve had walkouts, we’ve had things shouted to us from the audience. People have written or talked about how they relate to a character. During sex scenes you hear gasps, approval, disapproval. Some people will laugh uncomfortably. But that’s kind of the point of the play.”

As Melchior, he is rarely offstage. His favorite moments as an actor change constantly because the play, he says, is “really alive and different from night to night.” Currently, he enjoys a pivotal moment between his character and Wendla that leads to the song “The Mirror-Blue Night” and all of his scenes with Moritz, calling them fun because Melchior and Moritz are best friends who love each other and have each other’s backs but are very different people. And he enjoys the joyful “improvisational modern dance” that Moritz and Wendla do backstage before the final number, celebrating as the 2½ -hour show nears its conclusion.

And about those rock-concert-worthy microphones? Think of Melchior, Moritz and company as Everyteens, caught (as were all were) in the dramas of our own adolescence. Like teenagers everywhere, they are rock stars in their own private worlds.

Kathy Janich is an Atlanta theater artist and freelance writer. After more than 20 years in daily newspapers, she has found a joyous second career as marketing coordinator and dramaturg at Atlanta’s Synchronicity Theatre.