Stephen Sondheim’s masterwork is an entertainment with a dark soul that dances on the precipice of opera and musical theater.

::

The Atlanta Opera presents five performances of “Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street” on June 9-17 at Cobb Energy Performing Arts Center. Details, tickets HERE or at 404.881.8885. Discount tickets at PoshDealz.com.

::

MEAT PIES, hucksters, thuggery, urchins, and gore — such was Victorian London.

In 1833, an observer named Richard Rush wrote: “Accidents occurred all over London from a remarkable fog. Carriages ran against each other, and persons were knocked down by them at the crossings. The whole gang of thieves seemed to be let loose. After perpetrating their deeds, they eluded detection by darting into the fog.”

Residents came to understand that when the smog turned the color of pea soup — a particularly toxic cocktail — people and livestock would drop dead. Extreme poverty, carcasses in the street, raw sewage and child prostitution were commonplace. The original Sweeney Todd wasn’t just the tale of a psycho killer, it was a portrait of that place, and an entertainment for the souls who lived there.

In the throes of the Industrial Revolution, London’s population more than doubled. It just so happened that, with the advent of the printing press and advances in public education, literacy also rose.

Enter the ‘penny dreadfuls’

An enterprising Fleet Street publisher named Edward Lloyd capitalized on this new market by cranking out fiction for the rough-hewn masses. As Charles Dickens issued his classic serials, Lloyd echoed them with titles like Oliver Twiss and David Copperful.

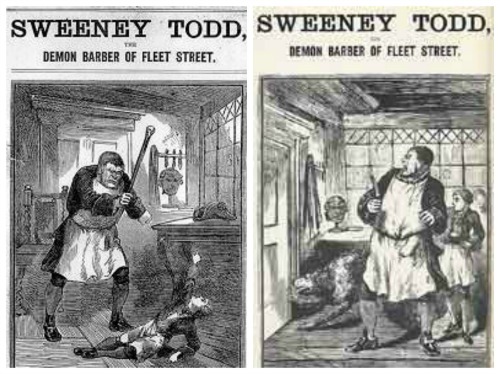

Gothic stories were particularly popular (think of A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities or Great Expectations). Issues of Dickens’ serials sold for a shilling, but Lloyd’s “penny dreadfuls” sold for 1/12th that price. The most famous of these was an original tale about young love and a monster named Sweeney Todd.

Sweeney was part of a serial called The String of Pearls: A Romance. Published in 18 installments in 1846/47, the tale was so popular, it hit the stage before the print series ran its course. Because 19th– and 20th-century scholars made little effort to preserve the penny dreadfuls, it hass been difficult to establish the story’s author. James Malcolm Rymer and Thomas Peckett Prest, Lloyd’s best writers, have both been credited at various times. Recent scholarship points to Rymer.

Sweeney became an icon to Londoners. Today, you can visit his Fleet Street storefront (the Dundee Courier building), and read his full biography online, including information about his supposed death by hanging. Historic documents do not support the notion that he ever lived.

Stephen Sondheim entered the picture in 1973 when he stepped into a London theater for a performance of Christopher Bond’s play Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street. Bond gave the misanthrope a tragic backstory and a trigger for his descent into madness, which became Sondheim’s entry point.

“What I did to Chris’ play is more than enhance it,” Sondheim said. “I had a feeling it would be a new animal. The effect it had at Stratford East in London and the effect it had at the Uris Theatre in New York are two entirely different effects, even though it’s the same play.”

Sondheim enlisted Hugh Wheeler to write the book, and worked with his longtime collaborator, director Harold Prince. Prince and Sondheim disagreed on the basic premise. Sondheim saw it as a revenge play. Prince saw it as an allegory for the social conditions of the Industrial Revolution. Probably, it is both.

Clearly, Sweeney has it in for Judge Turpin, but when he sings “There’s a hole in the world like a great black pit, and it’s filled with people who are filled with shit,” he’s condemning humanity, not just his nemesis. Dramatically speaking, he declares civilization an illusion (not such a stretch in that horrid place) and justifies what’s to come.

Sweeney Todd the opera?

Music doesn’t necessarily like to fit into boxes. You can make a thoughtful list of the differences between opera and musical theater only to follow it with dozens of exceptions. Sweeney works both ways, depending on the production and the cast. Opera singers train to cut through an orchestral texture and fill a large auditorium with their voices. And, they do it without microphones. The microphone enables musical theater performers to sing eight or nine shows per week without straining the voice, whereas operas singers need a few days’ rest. Often, it is the character of the voice that suggests a young singer’s career path.

Once upon a time, Leonard Bernstein took a chance on a young talent. He hired a 25-year-old Oscar Hammerstein protégé as the lyricist for West Side Story (1957). As co-creator of the landmark show, Steven Sondheim soon earned his stripes in the musical theater world.

Bernstein, a man well acquainted with the inner workings of opera and Broadway, later remarked: “I expected after West Side, that a lot of new young people would come in and take the next step, and the next step, and the next step, and by now we’d have had something that we could call the equivalent of opera — American opera. … But we don’t. The solitary exception is Steve Sondheim who does take a step with every show he does.”

Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street opened March 1, 1979, on Broadway and won eight Tony awards. Critics and audiences alike often consider it his masterwork.

Meryle Secrest, author of Stephen Sondheim: A Life wrote that Schuyler G. Chapin, formerly of the Metropolitan Opera, was in the house that opening night and said, “I would have put it on like a shot, if I’d had the opportunity. … Because it is an opera. A modern American opera.”

Five years later, Harold Prince staged Sweeney Todd at the New York City Opera.

Mr. Todd and Mrs. Lovett

At The Atlanta Opera, baritone Michael Mayes sings Sweeney, with mezzo-soprano Maria Zifchak as Mrs. Lovett, his deliciously amoral partner in crime.

Mayes says he creates a character like Todd by finding “the nooks, crannies and cracks in that person, then filling them with those things we have in common.” Almost everyone has felt revengeful at some point in life.

Although Mayes has sung a variety of roles, he’s most passionate about modern American opera. He has performed in pieces about the death penalty (Dead Man Walking), the Holocaust (Out of Darkness) and post-traumatic stress disorder (Soldier Songs). He has a name for work like this.

“I consider it opera with a social conscience,” he says.

::

Judith Schonbak contributed to this article.