FROM THE SLUMS OF ARGENTINA TO THE ATLANTA OPERA STAGE, THE ONETIME ‘VULGAR’ DANCE HAD A LONG ROAD TO ACCEPTABILITY

::

The Atlanta Opera’s “Maria de Buenos Aires,” part of its Discoveries series, runs Feb. 2-7 at Le Maison Rouge at Paris on Ponce, 716 Ponce De Leon Place NE. Sold out.

::

AT ONE POINT in his career, famed Argentine musician Astor Piazzolla tried to bury his history with the tango. He wanted to move on, to make a career change, and won a grant to study composition in Paris, in 1954, where he presented “kilos of symphonies and sonatas” to the famed teacher Nadia Boulanger. Things quickly became uncomfortable.

“I can’t find Piazzolla in this,” she complained to him. “You say that you are not a pianist. What instrument do you play, then?”

“I can’t find Piazzolla in this,” she complained to him. “You say that you are not a pianist. What instrument do you play, then?”

“I didn’t want to tell her that I was a bandoneón [accordion] player,” he recalled. “I thought, ‘Then she will throw me from the fourth floor.’ Finally, I confessed and she asked me to play some bars of a tango of my own. She suddenly opened her eyes, took my hand and told me: “You idiot, that’s Piazzolla!”

Humble beginnings

The tango does not come from polite society. Born in the slums around the Río de la Plata basin, its origins are murky — the urban poor are not the people history remembers. Within these seaport shantytowns were former African slaves, gauchos (farm hands) and hundreds of thousands of European immigrants. Several experiences bound these communities together: poverty, prostitution, the church and, curiously, knife-fighting.

The British naturalist Charles Darwin encountered these “compraditos” in the 1830s, noting that, although knife-fighters often died, killing was considered bad form. “Each party tries to mark the face of his adversary by slashing his nose or eyes,” he wrote, “as is often attested by deep and horrid-looking scars.”

The British naturalist Charles Darwin encountered these “compraditos” in the 1830s, noting that, although knife-fighters often died, killing was considered bad form. “Each party tries to mark the face of his adversary by slashing his nose or eyes,” he wrote, “as is often attested by deep and horrid-looking scars.”

These are the men — hardened, virile and saddled with hopelessness — who invented the tango.

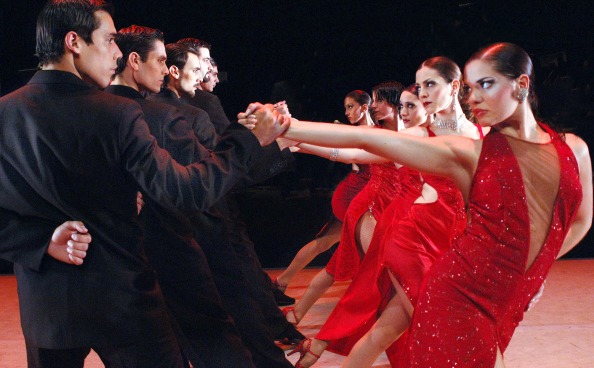

When performing, tango dancers’ torsos communicate through a tight embrace in which the partner, not always a woman, moves like the shadow of the leader. There is a longstanding tradition of men training for months or years with other men before they step onto the dance floor with a woman.

In the beginning, the establishment frowned upon dancing in an embrace as evidenced in an 1814 article in The Times of London: “We remarked with pain that the indecent foreign dance called the Waltz was introduced (we believe for the first time) at the English court on Friday last. … It is quite sufficient to cast one’s eyes on the voluptuous intertwining of the limbs … to see that it is indeed far removed from the modest reserve which has hitherto been considered distinctive of English females.”

Arriving in a wave of immigration from Europe, it is likely that the waltz and the polka fed into the evolution of the Argentine tango. Further evidence suggests that the characteristic “chan-chan,” a tango term for the snappy two-note stinger at the end of the number, came from the music of African immigrants, as did another tango predecessor, the habanera.

Enter the bandoneón

Around 1910, the bandoneón, a German-made accordion, reached Argentina. The instrument became central to the tango. Considered vulgar and low-class, the dance only gained acceptability in Argentina after it caught on in Paris about 1912 — and then it became a national symbol.

Piazzolla completed María de Buenos Aires in 1968 using a libretto by writer-tango musician-historian Horacio Ferrer. Swimming in surrealistic haze, Ferrer’s language touches upon modern life (the Beatles and hippies), and things local to Buenos Aires. The words of this “operita” might not completely make sense. But when the title character introduces herself, she tells you everything you need to know: “I am María of Buenos Aires, I am my town, María tango, slum María, María night, María fatal passion, María of love! Of Buenos Aires, that’s me!”

María is a metaphor for all those things. “The wee girl [who] was born on a day when God was drunk,” dies halfway through the opera, playing out a never-ending cycle of birth, death and resurrection. It’s the same cycle that ripples through the tango, the slum, the night, passion, love, Buenos Aires and the Catholic faith.

María is a metaphor for all those things. “The wee girl [who] was born on a day when God was drunk,” dies halfway through the opera, playing out a never-ending cycle of birth, death and resurrection. It’s the same cycle that ripples through the tango, the slum, the night, passion, love, Buenos Aires and the Catholic faith.

In life, María “dies” each time she sells her body: “And I’ll still burn another life for two coins.”

In death, she persists in spirit form until she passes into a baby girl: “Time’s been stolen; yesterday and tomorrow,” says a character called ‘A Voice of That Sunday.’ “She has been christened María.”

Like the tango itself, Piazzolla had to travel to Paris to make peace with Argentina. Gifted and ever curious, he soaked up everything from Bach, Stravinsky and Bartok to jazz. With Boulanger, he sharpened his technique and returned to Buenos Aires to experiment with the tango, which, at first, infuriated members of the old guard.

Combining elements of classical music and jazz, he gradually gained acceptance writing and performing a music he pioneered called “nuevo tango,” and spent the rest of his life composing and playing the bandoneón for audiences around the world.