Story by Noel Morris

There was a time when combining church and theater was considered an act of indecency. Early performances of Handel’s Messiah, for example, scandalized upstanding citizens of Dublin and London. The silent partners of 19thcentury opera were ever-present censors, functionaries who prevented composers from showing priests, biblical figures, crucifixes, and religious rites in the disreputable atmosphere of a theater. Depending on the degree of Church influence in a particular city, composers were perennially having to rewrite shows to gain a censor’s approval. Needless to say, creating an opera based on the story Salome was a bold move—even in 1905.

Incest was not unusual for the Herod family, which inspired this tale. Herod the Great, King of the Roman province of Judea (and villain of the Christmas story) divided his kingdom among three sons: Herod Archelaus, Herod Antipas, and Philip. Philip married his first cousin Herodias and produced a daughter. Herodias later deserted him for her brother-in-law Herod Antipas. Enter John the Baptist, who denounced the queen: “For John had said unto Herod, It is not lawful for thee to have thy brother’s wife” (Mark 6:18 KJV). Herodias was outraged. Threatened by John’s popularity among the masses, she convinced her husband, Herod Antipas, to have John arrested. According to the Gospels, it was she who persuaded her daughter to dance for the king and condemn John to death.

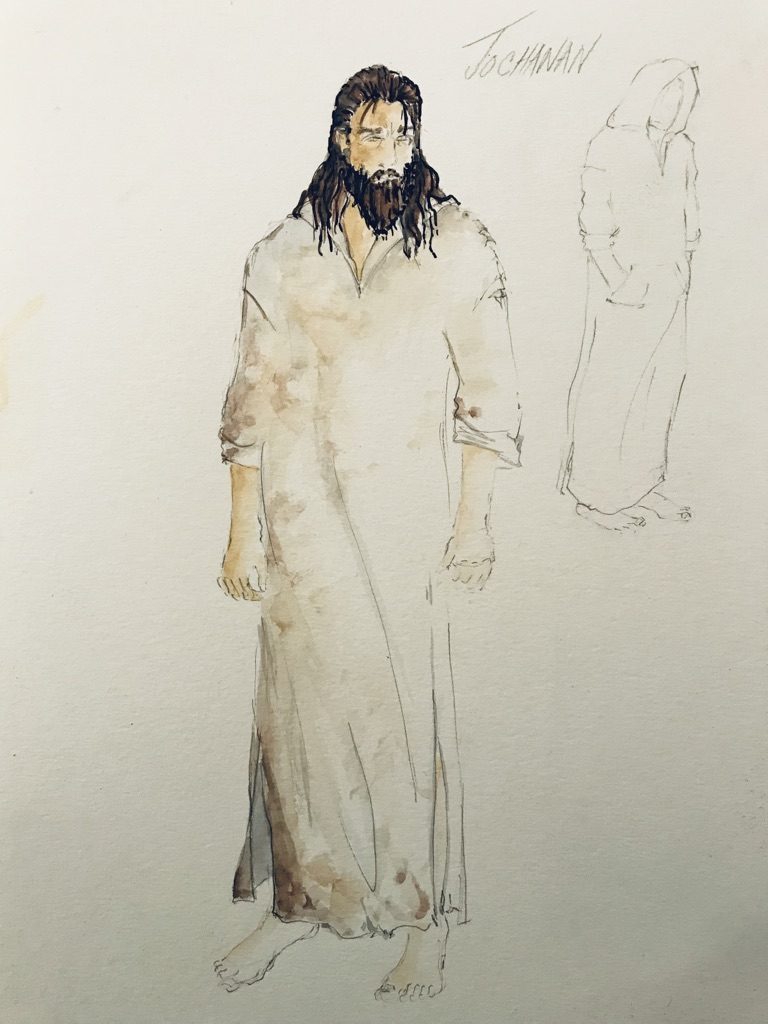

When first adapting this story for the stage, playwright Oscar Wilde took liberties with this part of the tale (perhaps a plot based on removing a political rival seemed too ordinary). Instead, Wilde created an intense psychological thriller by shifting the dramatic thrust onto the shoulders of a psychopathic teenager. Salomé entertains through shock: 1. a young girl locks horns with a ruthless tyrant, 2. a despicable father figure is consumed with lust for his stepdaughter, 3. the girl uses his lust, manipulating him to gain power over the object of her own desire—the holy man John the Baptist (in the opera he’s called Jochanaan, a transliteration of the Hebrew name).

Although Wilde was an Irishman, he wrote his 1891 play Salomé in French. The following year, Salomé went into rehearsal in London starring the legendary Sarah Burnhardt, but the Lord Chamberlain shut it down. Citing a ban on depicting biblical figures on the stage, an official decree prohibited any public performance of Salomé, a decision that remained in effect until 1931. Nevertheless, the play was published in English and in French. Fifteen years after it was written, Salomé finally had its premiere in Paris, but the playwright couldn’t attend. At the time, Oscar Wilde, who was gay, was in Newgate Prison serving a sentence of hard labor for “gross indecency” (homosexuality was not decriminalized in the United Kingdom until 1967).

In 1902, Max Reinhardt, an aspiring young director, launched his career staging a German version of Salomé in Berlin. By the time Richard Strauss saw the play, he had already read it and chosen the key of C-sharp minor for the opening line “How beautiful the princess Salome is tonight!”

Strauss was raised among the lions of 19th-century music. His father, Franz, had been a brilliant and well-connected French horn player. “Vehement, irascible, tyrannical” is how Richard described him. An ardent musical conservative, Franz Strauss loathed the musical shockwave issuing from the pens of contemporaries such as Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner.

“[Franz] Strauss is a detestable fellow,” Wagner quipped. “But when he plays the horn, you can’t be angry with him.”

It’s difficult to comprehend this schism in 19th-century music because none of it sounds radical to 21st-century ears – like trying to feel shocked by the sight of a woman wearing pants. Ironically, even as Franz Strauss championed the traditional, there was a modernist giant developing under his own roof. Richard, who would become one of the most successful composers of the coming age, later recalled having led a secret life in his father’s home: “I still remember very well how at around seventeen years of age, I almost feverishly swallowed the score of [Wagner’s] Tristan and fell into a frenzy of enthusiasm.”

At the age of 24, Richard Strauss wrote his first international hit, the tone poem Don Juan, a piece which aligned him firmly with the modernists. Through the tone poems, and an enormous outpouring of art songs, Strauss discovered his uncanny gift for turning visual images and narrative into sound. Looking toward the new century, he employed lush, unorthodox harmonies and opulent orchestration. During this time, he was making good money as a conductor, but still had his sights firmly set on opera.

By 1903, he had written three operas without much success. His Feuersnot (1901) had run into trouble with authorities over sexual content. In correspondence with Gustav Mahler, who was artistic director of the Vienna Court Opera, Strauss remained optimistic: “The censor in Vienna I find extremely funny! I can’t dare to hope for a ban. The advertising value of a ban by the censor would be the best thing that could happen to my little opera, since it wouldn’t mean that the performance in Vienna was actually cancelled, but just postponed.”

In fact, more than a century later, Feuersnot had yet to catch on, but Strauss’s comment certainly showed his attitude toward scandal. After all, his next opera would be based on a play that wasn’t even allowed on the English stage.

Using Hedwig Lachmann’s German translation of Oscar Wilde’s play, Strauss began serious work on Salome in 1903. He made a number of cuts to the play eliminating subplots and minor characters. In 1904, he continued work while on tour of the United States. Back home, he played excerpts for his father. “My God, what nervous music,” said the old man. “It’s as if one’s pants were full of maybugs.” Richard finished Salome in Berlin during the summer of 1905, three weeks after his father had died.

Reflecting the emotional power of the story, the role of Salome is demanding and particularly difficult to cast. The part calls for a singer with the stamina and voltage of a dramatic soprano (think Isolde or Brünnhilde), but with a lightness that befits the teenaged character. And then there’s the “Dance of the Seven Veils” — the singer must be able to infuse this ten-minute striptease with a potency that justifies just about everything else that happens dramatically.

Salome received its premiere in Dresden at the end of 1905. Reportedly, there were 38 curtain calls. Within two years, Salome saw some fifty other productions, and Strauss quickly became a wealthy man. In New York City, Salome was given two public showings in 1907 by The Metropolitan Opera before it was banned. The detractors, headed by the daughter of the powerful board member J.P. Morgan, attempted to enlist the help of English composer Edward Elgar. Elgar refused, stating that “[Strauss is] the greatest genius of the age.” While in 1909, Oscar Hammerstein’s opera house staged a production in New York and a touring company from Chicago brought the production back to the city in subsequent years, the Met’s ban on Salome remained in place until 1934.

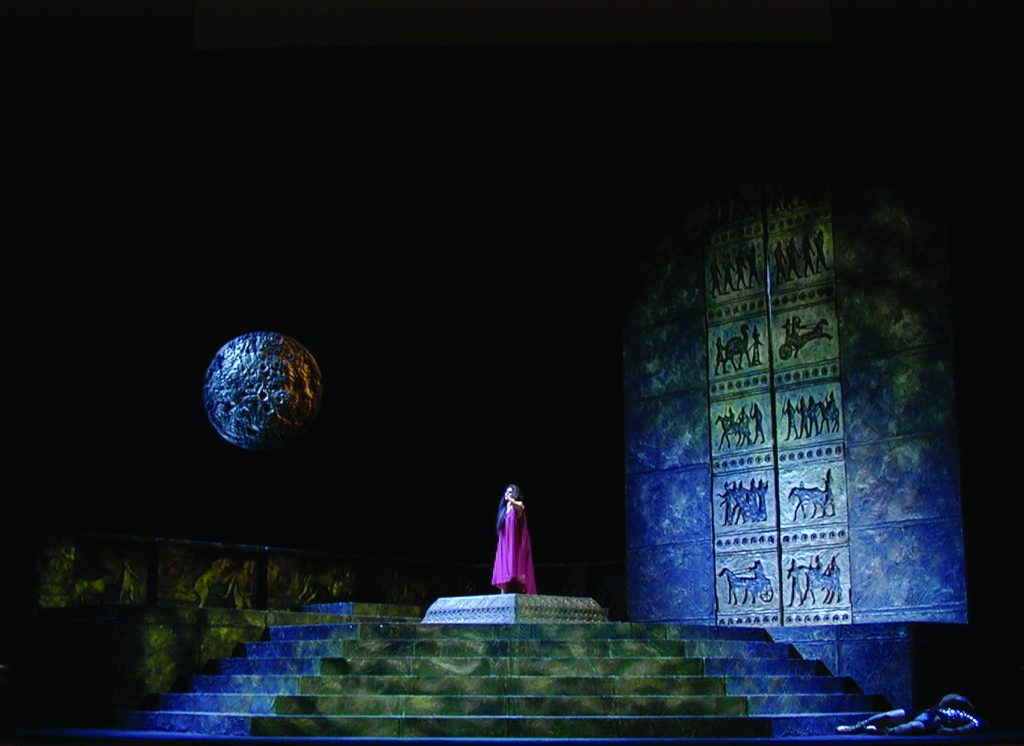

Feature photo: The Atlanta Opera’s 2003 production of Salome at the Fox Theatre. Photo by J. D. Scott.