Story by Noel Morris. Photos by Rafterman Photography.

Hollywood could learn something about strong women from Rossini. His Angelina of La Cenerentola is more than an accessory on the arm of some glib urban warrior. And she isn’t waiting for Mr. Wonderful to bring her out of her shell. She’s already out. She’s a believable human being who remains true to herself, and above all remains true to love. Not bad for an opera from 1817.

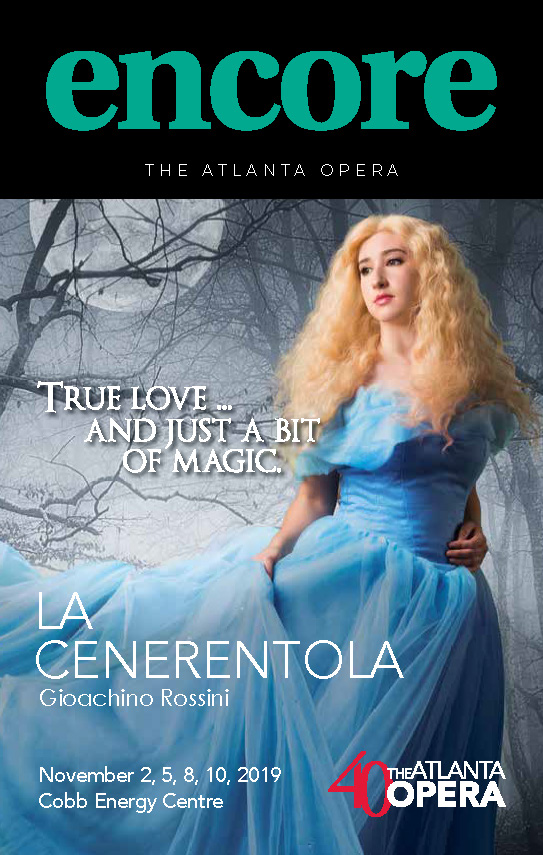

THE CINDERELLA STORY

Few things are as universally recognizable as a classic fairy tale. Fairy tales are timeless yet far away, connecting us to an age when things changed very little from one generation to the next; when few people traveled beyond a neighboring village, and when magic seemed more credible than science. For thousands of years, these folk tales were told and retold. Journeying the caravans and the sea lanes, they captured the imagination of weary travelers, crossing barriers of language and time to enter the collective knowledge of remote civilizations. Cinderella is one of these tales.

There are many variations. The ancient Greeks had a Cinderella story about a girl named Rhodopis. The ancient Chinese had one called Ye Xian. There are several in the One Thousand and One Nights collection. Getting closer to our own cultural memory, the Brothers Grimm wrote Aschenputtel, and it is grim. In this particularly Gothic rendering, the stepsisters hack off lumps of their own flesh in order to squeeze into the slipper. Also, Aschenputtel isn’t aided by a fairy godmother but a magic tree growing from her mother’s grave. Today, the best-known version of Cinderella is the one published by Charles Perroult in 1697.

LA CENERENTOLA & THE ENLIGHTENMENT

When Rossini took on Cinderella, he tapped into a stock character and used it as a framework to tell a contemporary story à la 1817 (Warner Bros. did much the same when they created the 2004 cult classic A Cinderella Story.). This is to say that La Cenerentola is not the Cinderella story you grew up with. There’s no magic, no glass slipper, and no fairy godmother. Rather, it is an Enlightenment opera created by men who were products of the “Age of Reason.” Cinderella’s pragmatism and strong sense of self reflect Enlightenment values — science, reason, equality, self-determination. She doesn’t win her prince by accident (losing a shoe), but keeps a cool head and remains steadfast in her character. In fact, she spurns the man she believes to be the prince. When her love says, “So you would be mine?” she doesn’t say yes, but gives him a bracelet that will lead to her humble existence beside the fireplace. “Plan, you must first search for me, meet me, see me, examine my luck.” In essence, she tells him: go figure it out and decide what kind of man you are.

When Rossini and his librettist, Jacopo Ferretti, conceived this story in 1817, Europe was still convulsing over the effects of the French Revolution. The people continued to push back against the power and privilege of the hereditary ruling class (notice the opera’s villains are three degenerate nobles). At the end of La Cenerentola, the prince chooses inner beauty over pedigree, becoming a champion of equality.

BEL CANTO

Bel canto, Italian words meaning beautiful singing, came to represent an era in opera which catered to a taste for vocal acrobatics. Singers were required to maintain a beautiful sound while singing higher and faster, sailing through harrowing clusters of notes with effortless aplomb. Rossini was a master of this style, writing music that leveraged the virtuosity of bel canto style toward dramatic—and a more profound—effect. In La Cenerentola, for example, he makes frequent use of the patter song, rapid-fire singing (Anthony Kiedis, eat your heart out) to evoke agitation, excitement or, in the case of Don Magnifico, silliness.

ROSSINI

Gioachino Rossini was born into a musical family in Pesaro, Italy. His mother was a working opera singer. When he was fourteen, he entered the conservatory in Bologna. In 1810, at the age of eighteen, he received his first opera commission. Incredibly, he composed another seventeen operas before writing La Cenerentola—all before his twenty-fifth birthday. He wrote La Cenerentola for a production in Rome in January of 1817. The full title is Cinderella, or Goodness Triumphant. Rossini finished the opera in just over three weeks, although he borrowed the overture from his earlier opera La gazzetta, which had premiered in Naples the previous September.

It would be difficult to overstate Rossini’s rock-star status. In 1823, the French author Stendhal wrote: “Napoleon is dead, but a new conqueror has already shown himself to the world; and from Moscow to Naples, from London to Vienna, from Paris to Calcutta, his name is constantly on every tongue. The fame of this hero knows no bounds save those of civilization itself—and he is not yet thirty-two!” From there, Rossini, who had already written thirty-four operas, went on to compose five more, ending with his massive drama on the subject of William Tell in 1829.

With that he was done. He lived another four decades but refused to write another opera.

Since that year, scholars and Rossini fans have proposed explanations for what one author called “the great renunciation,” yet none has managed to satisfy the curious or the heartbroken. Giuseppe Verdi, who was fifteen when Rossini quit, idolized the older composer and eventually came into his cadre of composer-friends.

The thirty-seven-year-old Rossini retired a wealthy man. We know he suffered depression and some unpleasant symptoms of gonorrhea, yet he frequently welcomed friends and fellow composers into his home. Pursuing a passion for food, he inspired a number of chefs to dedicate recipes “alla Rossini”. After his last opera, he wrote numerous songs as well as his famous sacred choral work Stabat Mater.

When Rossini died in 1868, Verdi organized a team of Italian composers (enlisting “no foreign hand”) to craft a memorial. Each composer contributed a single movement to a “Messa per Rossini”; Verdi himself wrote the “Libera me.” The performance, which had been scheduled for the first anniversary of Rossini’s death, was scuttled by political squabbles, and the manuscripts were returned to their respective composers. Six years later, Verdi repurposed his “Libera me” for his great Requiem Mass.