Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater visits the Fox Theatre on Feb. 14-17.

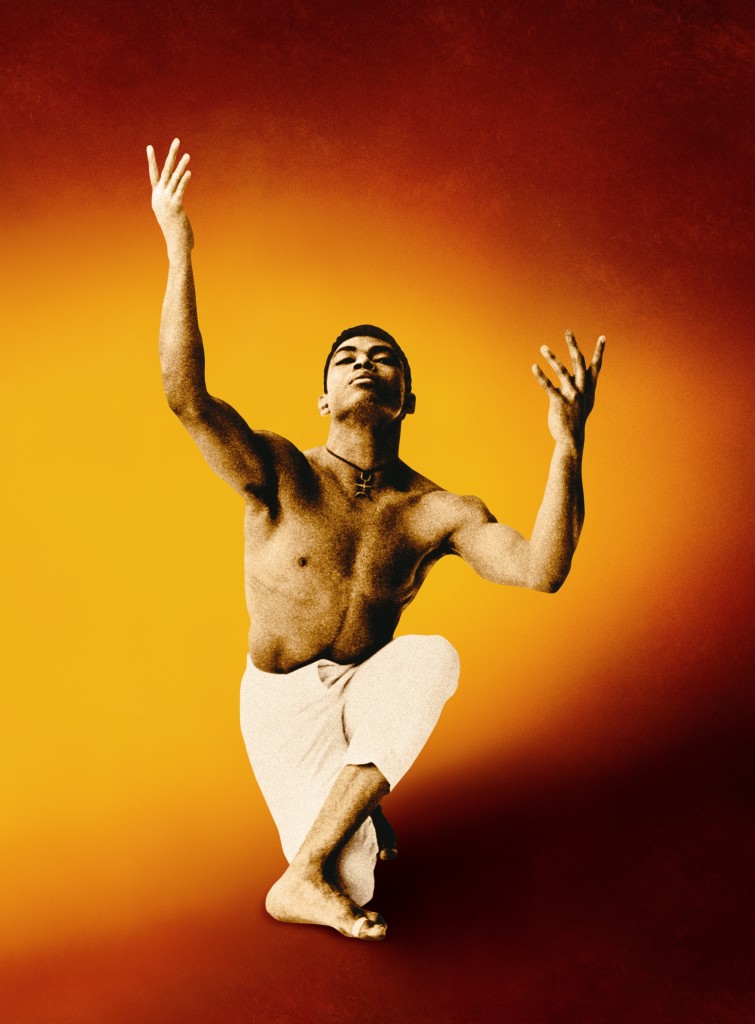

When 27-year-old, Texas-born Alvin Ailey launched his eponymous dance troupe in 1958, he did so in a different America. A first-class postage stamp cost 4 cents. The very first Pizza Hut opened in Kansas on $600. And less than half of U.S. households had a TV set.

Much has changed since then, but the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater has kept Ailey’s founding principles powerfully intact: modern dance that draws from other artistic mediums; strong, acrobatic performers; and a vivid illustration of diversity through movement. In its entire history, the company has had just three artistic leaders: Ailey (1958-1989), Judith Jamison (1989-2011) and Robert Battle, who took over in July 2011.

Battle, 40, a former artist-in-residence and company choreographer, is committed to Ailey’s past and its future.

“The company is a testament to the transcendent power of artistic expression,” he says. “I’m thrilled to further expand Ailey’s diverse repertory with new choreographic treasures that showcase the breadth of the dancers’ artistry while paying tribute to Ailey’s rich history.”

A rich history, indeed. But exactly how did this particular dance theater —one that has performed more than 200 works from 80-plus choreographers and moved critics to use phrases like “ecstatic movement” — endure and grow for more than five decades?

It started with a simple desire and a lot of early energy.

Segregation was legally banned in New York, when Ailey moved there in 1954 to perform on Broadway in Truman Capote’s House of Flowers, but it was still enforced, partially or wholly, in more than 20 other states.

He found the city a fertile place for a young artist, studying dance with such innovators as Martha Graham and acting with Stella Adler. But he felt unfulfilled in his growing ambition to include African-American culture in modern dance. Unable to find an outlet, he formed his own company.

Its repertory that first year featured seven works, four choreographed by Ailey, including Blues Suite, an his ode to the music of his Southern childhood. Still small, company members toured together in a single station wagon.

By 1960 nine new pieces had joined the repertoire, including the groundbreaking Revelations, perhaps the most widely seen modern dance in history. To date, Ailey dancers have performed it in 71 countries, and it has been seen by tens of millions live and on television. As the decade progressed, so did the company, no longer crowding into one station wagon but performing in countries around the world.

The 1970s were filled with innovative choreography and collaborations. The company received numerous awards, appeared at White House galas, performed at Studio 54 and toured the Soviet Union, a first for modern dance since Isadora Duncan’s famed days as a Russian sympathizer. The 1980s brought more honors, including a U.N. Peace Medal for Ailey.

Ailey died in 1989 at age 58. Jamison became artistic director at his bequest, guiding the company that Dance Magazine dubbed “recession proof,” due to its enduring popularity: A single live performance in Central Park in the 1990s, for example, drew a crowd of 30,000.

Today Ailey dancers are as popular as ever, welcomed in cities around the world as they do works new and old. This year, in addition to the its New York season, the company visits Miami and Chicago as well as Germany and France.

Its founder’s early desire for diversity in dance blooms perennially. Studios, schools, adjunct companies and college programs all bear his name.

It’s a solid legacy, and one with a high-flying future.

::

Therra C. Gwyn is a British-born writer living in the southern United States. She’s a columnist, blogger and feature writer whose other career endeavors include stints as a theatrical costume designer, a nonprofit marketing specialist and publicist for Peter Tork of the Monkees.

Great story. I love the last line. So true.

Thanks, Patricia. Please keep reading and commenting.